“Whoa, whoa, whoa. Aren’t you the guy who posted that article a few weeks ago about how nonprofits shouldn’t act like for-profits, and that donors shouldn’t be treated like customers?” If you read our last blog post, and you’ve made it this far into this one, you’re probably asking yourself that very question.

And to answer your question, yes, I am that guy. Two weeks ago I published a post here on the Fundraising Report Card® blog titled, “Nonprofits Aren’t For-profits & Donors Aren’t Customers.” And yes, I did publish this week’s blog post that you’re reading right now, “Nonprofits Should Act Like For-profits & Donors Should Be Treated Like Customers.”

So, your question “What are you doing, Zach?” is entirely appropriate… What am I doing contradicting myself just two weeks after the fact?

You see, the post from a few weeks back got a good bit of attention. A few thousand people read the article within a few days, and quite a few even commented with their thoughts. I also received a handful of emails — some more supportive than others, and ended up in a few back and forths on Twitter.

The response I received was overwhelming, but in a good way. So many people coming from a variety of diverse backgrounds all shared their thoughts on an important topic: how nonprofits should be perceived relative to their for-profit peers.

It was wonderful.

Yet, as those responses rolled in, I couldn’t help but question if what I had written was really “right” any longer. Should nonprofits strive to be more like for-profits? Should donors be treated like customers? What is the right approach?

Leaders in the field, individuals that I look up to and have learned from, took a polar opposite stance to what I had written. So, I did what I always do. I sat in front of my laptop, disabled my internet connection, (pro tip: this works) and started writing.

My conclusion was the same. I really do believe in my heart of hearts that nonprofits should not strive to act like for-profits, and that donors should not be treated like customers (which is what I wrote in the previous post). But, I realized almost immediately that just because I believe that, and took that stance, it didn’t necessarily make it “right.” So, when many folks (and I mean many) disagreed with my position I decided to listen and research even further instead of dismiss their opposing arguments.

My initial goal with the “Nonprofits Aren’t For-profits & Donors Aren’t Customers” blog post was to expel the notion that nonprofits should strive to be more like for-profits and that donors should be treated like customers.

The purpose of this week’s blog post is entirely different. Instead of batting down a certain perception, my goal has transitioned towards creating an open dialogue about how we (nonprofit professionals, industry vendors, consultants, etc.) should frame the industry landscape when comparing nonprofit organizations and for-profit companies.

Of course both sides of this argument are valid, and both are worth hearing out. It’s my hope that after reading this post (and the previous, if you haven’t already) you’ll be compelled to add your own thoughts to the discussion. Let’s start (and continue) a conversation about the very real issues our sector faces when it comes to rejecting or embracing our differences (and similarities) with for-profit businesses.

What if donors are customers?

At the root of this discussion is the idea that donors aren’t customers, which begs the question, if donors aren’t customers then what are they?

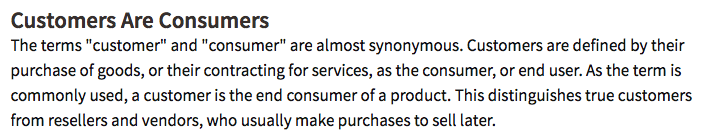

The definition of a customer (although I’m sure you can find dozens of alternative versions online) reads: “An individual or business that purchases the goods or services produced by a business.” If we agree that nonprofits are simply businesses that don’t share their profits (dividends) with shareholders (owners) then that definition suffices.

Pair that definition with this screenshot below, both of which come from Investopedia, (it doesn’t get much more for-profit than Wall Street, right?) and you have a cursory overview of what a customer is.

You can see above, one line reads, “customers are defined by their purchase of goods, or their contracting for services, as the consumer, or end user. As the term is commonly used, a customer is the end consumer of a product.” With this in mind, it is easy to characterize donors as simply a subset of customers. They’re the end users of whatever goods or services your nonprofit is offering and producing. Not the tangible goods or services you offer (the art museum is tangible, but that is what you offer to your attendees, not your donors), but rather the intangible “good feeling” you exchange when someone makes a donation.

What makes this exercise a bit more difficult is the fact that your nonprofit is selling something intangible. This can be, and often is overlooked. Claire Axelrad, from Clairification.com provides a great analogy in her comment from our previous blog post to help with the mental gymnastics:

When they [a donor] give[s] you something (e.g., money), it’s your job to return the favor. Retail stores give a tangible product or service. Nonprofits give an intangible ‘feel good’ in return. This is the foundation of the value-for-value exchange upon which all fundraising is based. If you don’t complete the exchange transaction, you’ll lose your constituents. I don’t care what you call them. They’ll go someplace else.

Claire makes it very clear; nonprofits sell that hard-to-describe “feel good” moment a donor has when they make a contribution. Don’t believe her? Really smart people have studied it.

Claire’s point is valid. It doesn’t matter if you’re selling something tangible, like a sweater, or something intangible, like an emotional response. Regardless of your offer, there is a value-for-value exchange, and regardless of the context of that exchange you have to complete certain components of the process to finalize a transaction and develop trust with a consumer. If you don’t complete the exchange (including post-purchase evaluation, more on that below) you will lose your “customer.”

It shouldn’t come as a surprise then that many for-profit business also sell intangible items. Take for example a luxury hand bag, or a pair of designer shoes. Is someone really interested in spending $5,000 for sneakers because the materials justify the price? Or is it instead because of the intangible value (social status) that comes from wearing $5,000 sneakers out in public?

I think it’s safe to assume most people who spend that kind of money do it for the intangible value — for the social status.

When put in this context, we can see that that nonprofits, similarly to retailers, sell intangible goods. This is one parallel between donors and customers that is often overlooked, it’s simply challenging to identify exchanges involving intangibles.

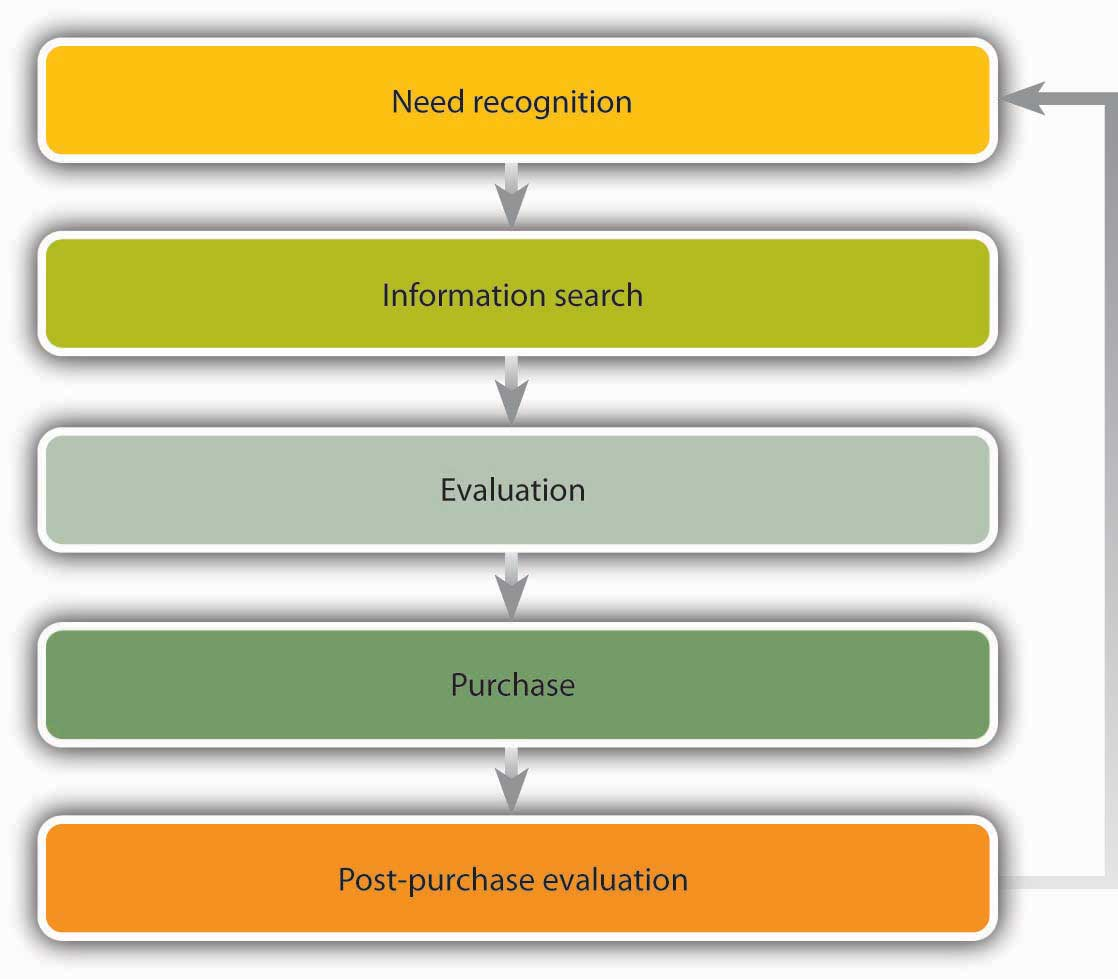

Donors and consumers share more common characteristics though. For example, their purchasing process is nearly identical. Both go through similar steps before executing a value-for-value exchange:

No matter how you slice it, donors and customers both go through these purchasing steps before making a transaction (purchase) and the evaluating it to see whether they would make the same transaction again. And this makes sense. In any exchange of money a consumer will not only want, but need to justify the exchange to themselves (and sometimes others) before committing to it.

The steps a donor goes through to make a donation may be:

- If I am going to donate then I first must recognize that I want to donate (consciously or subconsciously).

- I must develop a case for who I will donate to (consciously or subconsciously).

- I must donate and then evaluate my experience.

What about the steps a consumer takes before heading to the mechanic when their check engine light comes on? Perhaps it looks something like this:

- My check engine light comes on, it is time to get the car serviced.

- I must decide which mechanic I am going to go to.

- I must purchase their services and then evaluate my experience.

Are donating and going to the mechanic the same? Well, no, but are the underlying components of the decision making process the same? Yes, they’re strikingly similar.

With that in mind, nonprofit organizations may be able to look to their for-profit peers to identify tips and tricks to increase donor retention.

Think about it for a moment. Of the five steps listed above, where does our sector struggle most? It is unequivocally with post-purchase evaluation (or at least that is what the data suggests among first-time donors). To make matters worse, post-purchase evaluation is where donor retention is won or lost, which we all know has magnified impacts on your bottom line.

Maybe there is reason to look at for-profit companies to see how they do this so well?

Winning the Post-purchase Evaluation

Donor retention rate most closely parallels the activities that occur in the “post-purchase evaluation.” This is where both nonprofit and for-profit businesses either thrive or die. A donor or customer will always be faced with a few questions after they make a purchase:

- How was that experience relative to other purchasing experiences?

- Will I do that again?

- Would I recommend that to someone else? (Or would I dissuade others from it?)

Depending on how the post-purchase evaluation plays out, a donor or customer may either renew their purchase or find a different solution. In some cases, when the post-purchase evaluation provides either great elation or extreme dissatisfaction, a customer or donor can even influence the buying behaviors of others.

Great customer service and exceptional customer-centric support can help boost and maintain high retention rates , while poor communication, lack of engagement and a myriad of other factors can cause the number of customers who return to plummet.

Nonprofits should strive (and already do) to emulate successful for-profit retention strategies. Post-purchase customer engagement and “stewardship” are unbelievably important, and it is worth noting (and implementing) what for-profit businesses are doing right to build, maintain and grow those relationships.

Take for example a for-profit concept called the “loss leader strategy,” which simply entails, “[selling] a product or service at a price that is not profitable but is sold or offered in order to attract new customers or to sell additional products and services to those customers.” Many for-profit companies willingly lose money on their first transaction with a customer because they know they will make up the difference (and then some) with profitable upsells and cross-sells in the future.

Upselling and cross-selling are two components of the for-profit retention strategy that could (and do) have potential in the nonprofit sector.

Upselling is simply, “a sales technique where a seller induces the customer to purchase more expensive items, upgrades or other add-ons in an attempt to make a more profitable sale.” More on that here.

Cross-selling on the other hand is, “the action or practice of selling an additional product or service to an existing customer.” More about that here.

Both upselling and cross-selling increase customer retention. By increasing the financial commitment a customer makes they will be less likely to leave and find a different solution. Once you’ve made an investment it’s more difficult to change course.

This same concept can be applied to donors. Think for a moment about the YMCAs of the world. Their whole fundraising model is that members of their fitness club should become donors. This is basic cross-selling.

From what I’ve learned working with development staff at different YMCAs, this isn’t really the reality. Most members don’t become donors and many never contribute at all, but the concept is still there. If the YMCA does “crack the code” on how to consistently convert members to donors, retention will go up, all thanks to cross-selling.

So what does all of this mean for me?

Are donors customers? Should my small-shop NPO try and act more “nimble” and “agile” like a for-profit? Does any of this really matter to me right now?

These may be a few of the questions you are asking yourself at this point, and all with good reason. Hopefully some of these questions will help further the conversation surrounding this topic, and ultimately around how to increase donor retention. But one overarching takeaway that I hope you have from reading this is more mundane and simple: you can make an argument for anything.

Are donors customers? I’m not 100% sure, but I do know one thing, donors are people, just like customers are people. Donor or customer, we’re all looking for the same thing: the best experience, benefit and relationship we can get when making a value-for-value transaction.

Should nonprofits be more like for-profits? Who knows. Struggling organizations (nonprofit or for-profit) should strive to implement strategies that successful organizations are using. There’s no silver bullet. It doesn’t matter if you’re selling cars like my father (Hi, Dad) or selling an emotional experience, if you’re striving for success you should emulate what other successful organizations are doing.

So, if you’re taking your car to the mechanic or contributing to your alma matter, you’re looking to be treated with decency and respect, and to be seen as a real person, not a mobile ATM with dollar signs written on your face . For-profit, nonprofit, donor, or customer, it doesn’t really matter. Remember these core principles about treatment and you’ll be off to a good start.